Whenever a member of our team wraps a speaking engagement, after the public Q&A session, the CEO of a company invariably pulls us aside and in a half-whisper asks, “How do I know what my company’s worth?” This is usually hotly followed by, “What can I do to increase the value? When is the best time to sell, and how long will I stay on after I sell?”

There are entire books devoted to answering these questions, but let’s see what we can do in a few paragraphs. Let’s start with this:

WHAT’S MY COMPANY WORTH?

All merger & acquisition (“M&A”) transactions are valued on two fundamentals – the return a potential investment can yield and the perceived risk of getting that return. It doesn’t need to be more complex than that. Simply put, M&A makes sense to an acquirer when the cost (and risks) of securing additional revenue outweighs the cost of building the business organically.

Buyers initially focus on the potential earnings from an acquisition target. So, what exactly are earnings? The most common measure is EBITDA – Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. Because a buyer may have a different tax rate and a different capital structure, they exclude the target’s unique tax rate and interest payments. Similarly, depreciation and amortization are non-cash expenses, and companies may have varying accounting policies regarding how items are depreciated or amortized, so buyers typically look at earnings before these non-cash expenses. Thus, EBITDA is an attempt to measure cash flow from the business on an apples-to-apples basis.

In order to calculate EBITDA, start with net income before corporate taxes, add back interest expense, depreciation, and amortization, if any, to arrive at EBITDA. After all this work, this is a great place to stop, take a break, and get a cup of coffee.

ADJUSTING YOUR EBITDA

Many CEOs of privately held companies run expenses through the business that would not necessarily be incurred by a new buyer. These might include family members on the payroll, the one-time legal expense for an issue the company had last year, or the 30-foot Wellcraft boat the company uses on weekends as a “research vessel”. There are many others, and it takes a thorough review of your financials to prune out these unusual or non-operating expenses.

Because of these, we want to calculate “Adjusted EBITDA”. Starting with your financial statement EBITDA, add these extraneous expenses back. Be prepared to justify these addbacks because buyers will always be suspect that the expense was really necessary to generate cashflow.

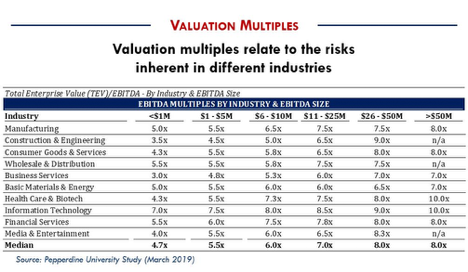

The next part appears relatively simple, but in reality, has complex math behind it. Look at the table below and multiply your Adjusted EBITDA by the respective EBITDA multiple given your industry and EBITDA size. For example, if you own a healthcare company with $1 million in EBITDA, multiply it by 5.5x and the initial valuation is $5.5 million. This is BEFORE the multiple is handicapped for perceived risks.

But what is this magical table? It is a summary of implied valuation multiples based on a large survey of actual sale transactions (“comps”), in this case compiled by Pepperdine University and published in the spring of 2019. The business school conducts a survey each year of investment banks, CPAs, and various intermediaries involved in the sale of companies.

A complete or formal valuation will include other analysis and computations, but this provides a thumbnail value range for your company. Comparing changes over multiple years also reveals some trends. Higher growth industries such as information technology and biotech have higher multiples while low growth industries such as construction have lower multiples. In general, higher growth gets a higher valuation. Since buyers are paying for future cash flow and growth results in higher profits, it makes sense they would pay more.

Notice how the values increase from the first column to the third column, In general, the larger the company, the higher the valuation. Larger companies tend to have more “quality” earnings, such as: complete management teams, better accounting systems, and more thorough business processes. In other words, there is less perceived risk that some unforeseen negative event will threaten the cashflow. Similarly, a smaller company may be dependent on one or two key employees or customers, and if something happens to one of them, earnings will likely suffer.

In addition to projecting earnings, buyers assess the risks to the earning and those risks decrease the valuation. Some of these risks are:

- Customer concentration as a percentage of sales

- Key personnel, such as a key executive or CEO-owner who is critical to the performance of the company. This also includes important personnel that have not been secured with employment agreements.

- Poor accounting and record keeping

- Risk of technical obsolescence

- High on-going investment in equipment

CEOs need to continually work to reduce the risks in their companies. This will, in turn, preserve if not improve the multiple applied to the Adjusted EBITDA number.

When it’s distilled down to its essence, a company’s worth is impacted by any decisions that boost its EBITDA or reduces perceived risk to the buyer; all within the purview of the CEO and not really so mysterious.

Patrick Morin is currently a Partner at Transact Capital. He joined the firm as Managing Director in 2012. Patrick brings with him a wealth of experience in capital raising, deal-making, strategic advisory to CEOs, marketing and revenue generation, along with investment banking and business ownership. As a prominent speaker to industry groups and business, Patrick is well connected to many well-known business leaders throughout the U.S.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Content provided by Transact Capital. Transact Capital is a Sponsor of Virginia Council of CEOs.